November 25th 2023

Acro Scientific Products Co.

Acro Model R

Between World Wars, names like Kodak, Graflex, Ansco, and Argus stood out in the American photographic world. That is only a small part of the story. Quite a lot of others took their chance with this growing market, but only a select few really tried to make something their own. Perfex, Ciro, and Universal come to mind when you talk about the more unique, middle and upper tier American made cameras. However, diving even deeper within that, lies a smaller subset.

This is a niche of companies that created one or two cameras, and had great potential. One example is Clarus, who created a very capable camera but could not quite grab a hold of the market due to timing, quality control, and ultimately their own doing. A very similar story played out for the Acro Scientific Products Company. A strange and short lived camera manufacturer, with a convoluted and somewhat obscured history. This is the story of the 1940 Acro Model R.

The Mystery of Acro

It’s truly astounding how many companies used the name Acro in the 1940s and 50s. From Acro Products Co. who made Acrosound linear transformers, to a brand of numbered window tacks, Acro Precision Machines, a metal fabrication tool company Di-Acro, and even a medical equipment company named Scientific Products. That is only a brief portion of what I was consistently running into. Lots of dead ends, re-writing sections, and new discoveries. I found a lot of information out here, and the journey was an interesting one. Be warned that this history section will be quite long!

With a name like Acro Scientific Products, it’s hard to imagine anything straying too far from a warehouse that sells beakers, flasks, and bulk chemicals. Very little is documented about this company and what they sold or who they worked with. After a countless amount of research, I believe I have found some answers. But before that, you will need some context.

The Model R was an interesting camera for the time. Using the 1912 introduced 127 roll film, this format was gaining popularity again in the late 30s, as more and more manufacturers were making smaller and inexpensive cameras. Out of this era, a particular style of camera was seemingly becoming the standard. This was thanks to the moldable and customizable wonders of Bakelite and the introduction of the 1936 Argus A.

Looking at the Acro Model R, it was not the first of its kind. The market already had two very similar cameras in the late 30s and early 40s. The Falcon series from the Utility Manufacturing Company in New York, and the Detrola series from Detrola in Michigan. These two companies used a larger Bakelite body, helicoid, Wollensak lens and shutter, standard viewfinder, and a removable back. Acro seemed to take bits and pieces of each of these designs, like the rotary red window cover and extinction meter from Detrola, and the table stand and focusing ring design from Falcon. This camera was a copy of each of those without a doubt, but it had something that set the Model R apart. Not only just the price, but a rangefinder.

In the American market, the Model R was the only 127 rangefinder in 1940, and stayed the only one for almost two decades until the late 50s Revere Eye-Matic EE. What made a 127 rangefinder appealing was the increase in quality from 35mm, without having to make the jump to 120 film. A comparable 120 camera at the time would have been more then four times the price. Not to say the Model R wasn’t expensive. Within contemporary ads, the Model R would go for 15.00 USD for the f/4.5 lens and 18.50 USD for the f/3.5 lens version. That was around 318 and 392 dollars in 2023; not a small sum even today. Versus the competition, the Model R matched or beat the price of other middle tier Falcon and Detrola cameras, including an extinction meter and non-coupled rangefinder. It would have been seen as the better deal and arguably the better camera.

Acro took out a few large ads with Popular Photography in 1940, as well as a page in the 1940 Sears Catalog, advertising the Model R. This I believe is where they would have found the most success, being a mail order company themselves. Sears even picked up the Model R for one of their own ‘house brand’ Marvel cameras, which would not have been a small feat. It was boldly included in the catalog from 1941-42 as the Marvel Minature Camera, toting the low price and variety of features. After 1942 the Model R and Acro themselves seemed to fade from advertisements and catalogs as America was entering World War II.

Acro Scientific Products Co. was said to be a part of the ‘Chicago Cluster’ of camera brands and makes, owned or working under Jack Galter of Spartus fame. He created quite the empire, and skirted around legal grey and not so grey areas for an unprecedented amount of time. He sold a lot of similar cameras under various names and companies, but all were of a Galter production. There is no solid evidence that Acro was a part of this conglomerate, other than a few name associations. So I decided to find out.

At the start of my search, I chose to see if there was a listing of an address. Within a few of the ads in Popular Photography, there was an address of 1414 S. Wabash Ave. in Chicago Illinois. You can find out a lot with an address, so I thought a phone book would be a good start. Scientific Products is an incredibly vague term, but they were first listed in the 1940 Chicago Red Book Yellow Pages under camera mfg. and wholesale. They paid a bit of money to get a bigger/bolder typeface on the page, proudly stating their name and address. Strangely enough, this would be the only mention I could find of Acro, not being present in the 1939 or 1941 phone book under this category. A dead end, but I learned something. Being listed shortly most likely means they changed product categories, were purchased, or possibly moved.

My next lead was the building itself; there was likely to be a record of some sort. 1414 S. Wabash Ave. started out as the Central Market Furniture Building in the early 1900s, later being divided up and rented to a large number of companies. No additional information, with only partial incomplete records available, but today it still stands as a rather plain looking storage facility. One dead end after another, but what about the camera itself? When a company outsources multiple parts of a product, whoever is manufacturing it will more often than not put a maker’s mark onto it. This may not be done too often today, but industry in the early 30s and 40s was still specialized and not often outsourced. Within the ads of the Model R, it stated the camera was 100% American made, so tracking these pieces down may lead to records or accounts of working with Acro.

First I started with the most complicated and specialized piece of the camera, the shutter. Right away you can draw similarities to other cameras like the Ciro 35 and Bolsey B2. These cameras used self charging shutters, all with a particular size, trigger location, and speed range. At this point I wanted to be sure, so I decided to contact someone who might know.

Wollensak shutters are indeed made in America. I stumbled across a wonderful source online that has archived a lot of the engineering documents. They created a database logging most if not all of the shutter and lens combinations used. I reached out to AlphaxBetax and talked to Bill to see if he possibly had any documentation on Acro and to double check if this was in fact a Wollensak shutter. No records that he could find, but the shutter was most likely a pre-war size 0 (zero) Alphax Jr. from around 1940 to 1941. Due to an uncoated lens and the shutter’s chrome and black design. Considering the earliest ads I could find were from 1940, this would line up!

Wollensak made the shutter and lens, but what about the other parts of the camera? Comparing the Model R to the Falcon and Detrola cameras, it seems that the body was a completely different design internally, and made in a different factory. There was a makers mark inside the body, labeled as TRCO. An acronym of some sort, but something to look into. From railroads to tradable stocks, everyone seemed to use this abbreviation. After a lot of digging I found one that might make sense. A single mention of a company using this acronym when being sold in 1974, the Tyer Rubber Company. I looked into this business for a very long time, trying to decipher marks on other products but came out empty handed. So I decided to talk to someone at the Andover Historical Preservation site, where this TRCO information was.

They were incredibly helpful, and sent me to the Andover Center for History and Culture site for additional help from their research staff. I sent the makers marks and they helped me look deeper into Tyer and if they possibly molded the body. However, after we corresponded a few times it was clear that the mark was not from them. As luck would have it, something one of the research assistants pointed out to me would lead me to another source. The emphasized ‘R’ on the mark, would not have been congruent with the other marks found on Tyer made products.

Back to square one and looking into TRCO, I decided to limit the search to companies before the 1970s along with another thing one of the researchers told me. Look into companies in Illinois with that acronym. I did just that and searched for a long while until I actually found it. This was an abbreviation for The Richardson Company, a plastics molder around since the 1800s in Illinois, abbreviated as tRco. A success and a failure, as the company's history and where they are today is not very clear. What now? The rangefinder was a unique device, that also had a makers mark from National - Chicago, most likely referring to National Steel, but that would not help me either.

I decided to look into Acro Scientific Products yet again, this time doing my best to find anything else they might have made. After changing up my search to focus on 'ACRO' and the 1940s, I finally found some more things! The first was a record, a physical one. The record was one that you could record yourself known as Recodiscs. I also found a horrid looking bit of Americana, a cardboard Statue of Liberty clock. So they did make other random products, but the next one would lead me to the answer in multiple forms. A projector and more importantly the application for a patent. Let’s start at the beginning one last time.

Within the November of 1935 segment of ‘With The Wholesalers’ in the Radio Today periodical, wholesaler and distributor Commonwealth Utilities Company was highlighted, stating that they moved to 1414 S Wabash Ave. in Chicago Illinois. They were greatly increasing in size selling Atwater Kent Radios and Gibson Refrigerators in the Midwest and recently moved to a larger space. Samual E. Schulman was president of Commonwealth Utilities Company from the 30s into the 1950s, stating they sold photographic equipment, along with radios, and phonographs. He is a bit of an interesting character, and seems to have made a fair bit of money with this company and his other business ventures. With the evidence of a Yacht of his registered for Chicago in 1944. The sales manager Walter O'Halloran was a person of note as well, deemed as radio royalty and a veteran in the mid 20s radio sales game. O’Halloran moved between a few companies like the All-American Mohawk Corp. and Harry Alter Co., until landing at Commonwealth in the 30s.

The Commonwealth Utilities Company’s November 1939 trademark would be granted in February of 1940 under Class 26 (Measuring and Scientific Appliances) for cameras and lenses in Chicago. This trademark was for none other than the name Acro. Around the same time, Commonwealth created the Acro Scientific Products Company and started advertising and writing to magazines about the new Acro Model R. In the February 1940 edition of Popular Photography, the Trade News section would report on the ‘New Acro Camera’ along with the addition of a full size ad a few pages later. Acro would continue to advertise into 1941 where they would move into selling directly to stores and Sears. Throughout the 1940s, within other stores ads in the ‘used cameras for sale’ sections, the Model R would hold some value and find a spot until the 1950s.

Another projector would lead to the final answer to this mystery in the form of an ad. A leaflet for sale online of a scandalous variety shows an ACRO branded projector that projects 35mm and 1/2 127 film, featuring 'Scientificaly' used in the description a few times. This led me to look for more Acro Projectors. On a whim, I looked up Spartus projectors and found my answer. Acro Scientific Products was not part of the Chicago Cluster, but possibly was bought in the 50s.

In 1951 Jack Galter sold the Spartus Company to his sales manager Harold Rubin, where he changed the name to Herold Manufacturing Company for a brief time. This was the same name on the projector, branded as Acro. Looking closer, it seems ‘type G and J’ body styles of the Photo Master, Rolls, and Remington 127 Herold made cameras used very similar winding knobs as the Acro model R. There even was an Acro and Acro-Flash camera made in the 50s with a different looking logo. It could be that they had the same source for a few components, but from what I could find, the Commonwealth Utilities Company moved to another building in the late 40s or early 50s and the Acro brand seemed to fade shortly after. My best guess is Acro was under Commonwealth until 1951, being purchased by Harold Rubin around the same time and folding into the Spartus world shortly after.

One last thing to note is there was a Model V, which only had a simple viewfinder and two knobs on the top of the camera, removing the entire rangefinder metal assembly with everything inside it. Acro also sold just the rangefinder as a pocket sized component to pair with another 127 camera. Clever, if someone bought the other brand they could still sell them something they were missing.

An incredibly convoluted history and one that is still not complete, but hopefully I was able to shed some more light on the history of the Acro Scientific Products Company. Thank you to everyone who helped me in the research for this article, along with Ken at the Eastman Museum Library and Archives, and Christine at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History for scouring their archives for additional information.

The Scientific Camera

In the 1930s and 40s, the standard Bakelite camera shape and design was set by Argus. The Model R followed this tradition with similar lines, shapes, and styling. An all black body, matte steel parts, and decent weight, made it fit in perfectly with the similar Falcon and Detrola models. This created a sort of greatest hits of each of its predecessors, differing with the most important feature, a rangefinder.

To load film into the Model R, you will need to push the catch on the rear of the camera and hinge the metal back to the right, removing it completely. There will most likely be an empty spool to the right, where you can pull the knob on the bottom right down to release it. Lift the winding knob on the left side, inserting the empty spool. Replace a spool with film on the right, pulling the paper over to the left. Thread the leader onto the spool and wind to create tension. Reattach the camera back, making sure the latches are seated correctly. Rotate the disc on the back until you see two red windows and wind until you see the number ‘1’ in the right most ‘A’ window. The Model R is a half frame 127 camera, leading to 16 pictures per roll. No commercial backing paper made had half size frame numbers added, so you will need to advance the film a bit differently than normal. You advance each printed frame number into both windows before you move on to the next number. Also make sure to rotate the disc on the back so you cannot see the red windows when you are not advancing, to help protect the film.

Next in the shooting process, you have the option of taking a meter reading with the included extinction meter. Look inside the larger rectangle window on the back of the camera and hold it about half a foot away from you. There are numbers printed on a gradually increasing density scale, with the largest number you are able to see being the light value. Transfer this number to the rotating calculator on the top of the camera, lining it up with the film speed you are using between an ASA of 3 to 200. This will tell you what shutter speed and aperture combinations would be the correct exposure.

To focus the camera, you would first need to look into the left most window on the back while rotating the farthest right dial on the top of the camera. The rangefinder uses one longer window on the bottom, with a smaller one on top that slightly intersects with the lower window. Turn the dial until the two windows line up and you will have a rangefinder reading from the dial.

With all of this new information, you can now take a picture. Transfer the distance to the focusing helicoid under the shutter, from infinity and 25 feet down to 3 feet. Set a shutter speed of 1/25th up to 1/200th and an aperture of f/3.5 (or 4.5) down to f/18 by rotating the small pointers on the shutters face. Compose through the viewfinder window on the back in the center, and use your right hand to trip the shutter release lever on the shutter. Make sure to wind to the next frame right after, as there is no double exposure prevention. A bit of an involved process, but something that is not too far removed from what you would do with a large format camera.

THE SPECS AND FEATURES

Shutter Speeds - time, bulb, 1/200, 1/100, 1/50, 1/25

Aperture - either f/4.5 or f/3.5 to f/18

Meter Type - extinction

Focus - infinity and 25 feet to 3 feet

Shutter - Wollensak size 0 Alphax Jr. shutter, self charging

ASA - calculator on top from ASA 3 to 200

Lens - Acro anastigmat (Wollensak Velostigmat anastigmat)

Flash Option - none

Batteries - none

Film Type - 127 half frame

Other Features - exposure calculator, table stand, non coupled rangefinder

The Experience

A few years ago, I ran into a very rough Model R and attempted to work on the camera. I broke a major part of the focusing component, the shutter was all sorts of broken, and I gave up not too long after. I really wanted to shoot with the camera and looked into finding another after I learned what I did wrong. My chance came a few months ago with a decent price for another Model R online, and I messaged the seller if they knew if the focus was stuck. They responded a day later, stating that it indeed was and they were just going to recycle the camera! I jumped in and still offered to buy it, and they said they would sell it to me for the fees and cost of shipping.

Once the camera arrived, it was in much better cosmetic shape but just as stuck. I dug out my other broken example and did a few tests on the helicoid again, not really sure what would free the mechanism. I’ve repaired countless Agfa cameras and their grease that turns to cement, but this was on another level. It turns out that in my many deep dives into research, this was a common problem with the Model R, and a problem that was known even in the 1940s. Within the 1947 edition of Consumer Union Reports, they covered a large portion of cameras on the market, sorting them into acceptable and not acceptable categories. The Model R focus was stated to be “stiff and difficult to adjust” and the camera barely made it into the acceptable category, stating that the “Cover over film window was very difficult to operate. ‘Acceptable’ only if focusing ring and film window cover work easily on sample you select”. This would prove to be foreshadowing on how difficult fixing the helicoid would be.

Previously I tried leaving the other helicoid in various solvents, heated it up in the oven, boiled it, and tried penitrating oil. Nothing worked even slightly, and as I was trying to pry the to halves apart in a last attempt, the main surface the shutter was mounted to shattered. The amount of force and various heating, cooling, and solvents must have made the metal brittle. Learning from my mistakes, I unscrewed the mounting plate from the body, removed the shutter, and soaked the entire helicoid in a much thinner oil. After a day, I used every ounce of strength I had to slightly turn the mechanism. It did not move.

Last year, I ended up purchasing a resin printer along with a print washer. This is a device that you pour denatured alcohol in and it agitates and mixes the liquid around. A solvent would work best if constantly moving around dried grease, so I thew the helicoid in for an hour. Afterwards, I could see small amounts of grease leaking out of the two halves not present before. I scraped it away, and repeated the process multiple times. Leaving it in the alcohol overnight, the next day I was able to slightly move the distance ring. For the sake of brevity, this took an absolute eternity of slightly pushing up the inside portion until it was able to separate. It turns out that there are no threads, its just two very tight fitting metal tubes… guided by a cut out track on one tube and a pin on the other. After separating the tubes, I cleaned them thoroughly and tried to fit them together again. There was no way in hell this ever worked correctly, they were not even close to being able to move. I had to pry them apart again, and this time I stripped the screws that held on the knurled distance ring.

Frustrated, I found slightly larger replacement screws and reattached it. After looking closer at the two tubes, one seemed to be much rougher cut than the other, leading to a slightly bumpy texture on the rounded surface. I ended up sanding the two tubes for far too long, trying to get them to be smooth and turning together. After I could freely move them together, I polished the two surfaces, greased the halves, and reassembled the camera. An extremely long process start to finish, but I believe that I may have the only focusing one of these around today. One last thing remained though. The rangefinder was all sorts of messed up on this example, but a quick swap, clean, and calibration of the other spare I had made for a fully working Acro Model R.

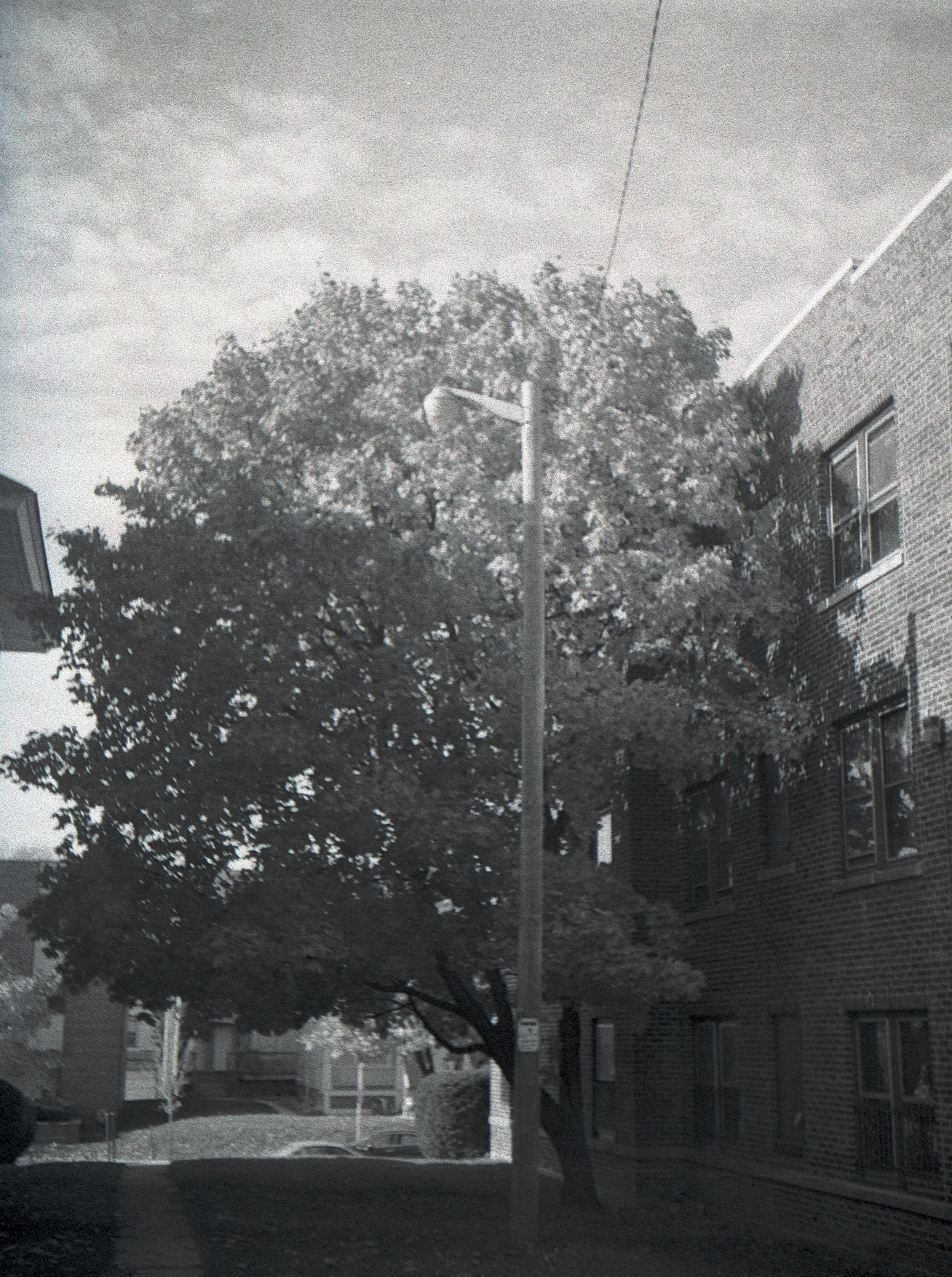

I was very excited to try this camera out, and I luckily had a new roll of color 127 film I had been saving for a rainy day. I loaded the camera and brought it with me on a visit to my parents. This was the first run of using the Model R, and I found myself accidentally moving all of the settings every time I took the camera out of my jacket pocket. Half the roll was unusable, but I got a picture of an autumn field I really quite liked. The focus was spot on, the shutter worked great, and the frame was perfectly level. An excellent first test, and I was really starting to like this camera. I also did not mind the vignetting on the frames edges, which only showed at infinity.

This is where I ran into a new issue, I didn’t have any more 127 film on hand, so I decided to make a film cutter. I found a 3d printable 120 to 127 film cutter online, and spent a couple of days printing out the different pieces. I chose to print both the cutter options where the leftover film was either 16mm or two 8mm strips. Cutting the film was not an easy process, rolling and rerolling the 127, and then loading a few Minolta 16 cartridges. A learning curve for sure, but the next weekend I was ready to shoot.

I took the newly cut T-Max 400, and went out on the bike trail. It was not my best choice of film, as it was incredibly bright out, and the Model R had a limited range. Some pictures were blown out completely, and I was still knocking the settings out of place when taking the camera out of my bag. That’s on me though. After developing, I had a few pictures I liked, but really wanted to see what this camera could do.

For one last test, I decided to cut a roll of Portra 400 I had in my freezer for ages. I took pictures at my aunt and uncle’s house during Thanksgiving, and finally got the shooting process down. Faster pictures of the playful dog were not too difficult, and I finally found a rhythm with this camera. I was left with a really great test of the Model R, minus a few light leaks, but there was one picture that stood out. The last color picture on the roll of their dog Bella. At the closest focus of three feet, it really showed me how sharp the lens was, and how pleasant the Wollensak lens renders out of focus elements.

With other 127 camera choices, you have a multitude of fixed focus and scale focus cameras, but only a select few that were well made. The likes of the Yashica 44 come to mind, but I would like to throw the Model R in there as well. After a lengthy process of not only research but repair, I am left with a camera I truly enjoyed shooting. The history of the camera alone was fascinating, and it was a shame they did not expand upon this camera or make anything else. A company with a lot of potential I would say. The Acro Model R is an exceptional and unique camera that deserves a spot in history and collections alike.